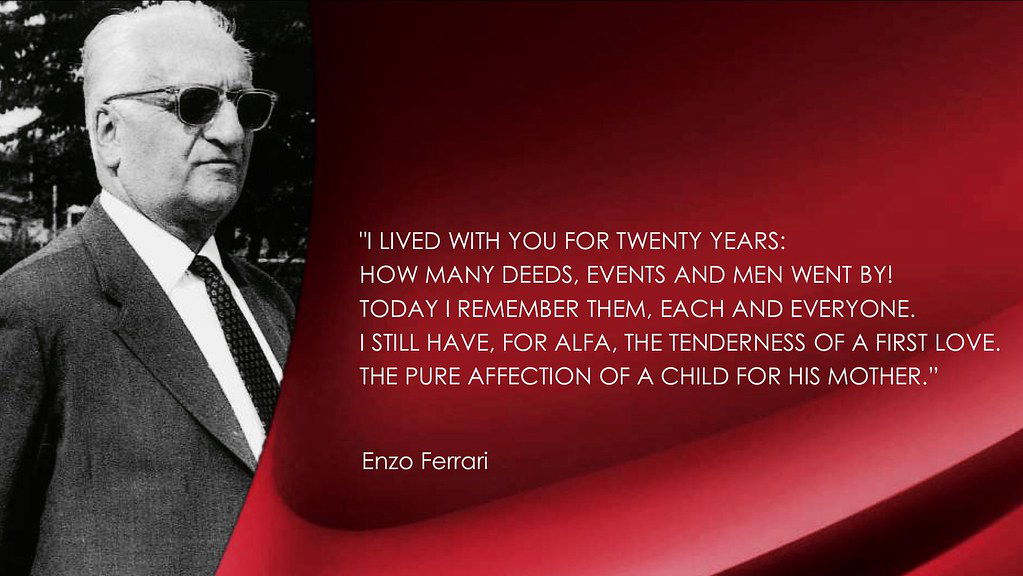

Enzo Ferrari's journey towards founding Ferrari Automobili began with an unexpected turn of events in 1939. After a two-decade-long racing relationship with Alfa Romeo, Enzo Ferrari found himself at a crossroads.

His association with Alfa Romeo had been a mix of success and turbulence, but it came to an abrupt end on September 6, 1939, when Alfa chief Ugo Gobbato terminated his contract as a senior advisor, well ahead of its official expiration date.

Gobbato's decision effectively dissolved the renowned Scuderia Ferrari, a racing team closely tied to Alfa Romeo, and this decision came at a significant cost to the automaker, given the contract's termination conditions.

Related Reading: A Concise History Of Ferrari S.P.A

“In The End, I Was Sacked”

In a formal statement, Gobbato cited Italy's expected entry into World War II as the reason behind this abrupt termination. He expressed regret over the circumstances but also conveyed appreciation for Enzo Ferrari's two decades of service to Alfa Romeo.

He emphasized that the liquidation of their partnership had been amicable and mutually satisfactory. Enzo Ferrari, however, summed up the situation more succinctly, saying, "In the end, I was sacked."

This dismissal marked the end of his long-standing association with Alfa Romeo. He sold the racing cars to Gobbato and was left without a clear path forward. Still, Enzo Ferrari was not one to be deterred.

With the settlement from his two-decade partnership and his personal savings, he embarked on a new mission: transforming the Scuderia into a small car factory. Ferrari's severance payment from Alfa Romeo provided him with a substantial sum, enabling him to invest in a downtown Modena apartment building.

The public announcement of this transition was straightforward: "Ferrari, after mutual agreement with the management of the make, resumed his freedom with respect to Alfa Corse, and is now setting up, in the premises that were already home to the Scuderia, a workshop for repairing cars. Racing is, for the time being, set aside."

However, this apparent departure from racing would prove to be temporary. Although the agreement with Alfa Romeo prevented Ferrari from rebuilding his Scuderia or participating in the racing world for four years, he was determined to find a way back in. Enzo Ferrari discovered a loophole that allowed him to circumvent these restrictions.

The Call Of Mille Miglia

In September 1939, he founded a new company called Auto Avio Costruzioni (AAC). Initially presented as a workshop for repairing cars, AAC operated from Ferrari's existing headquarters at 11 Viale Trento e Trieste in Modena.

In reality, this new venture, led by Enzo Ferrari and joined by skilled engineers and mechanics, was primed for design and manufacturing work. Repairing cars would be a secondary endeavor.

Enzo Ferrari could not directly compete in races, but he realized that if his name was not associated with the manufacturer or its products, he could still be part of the racing world.

This innovative move set the stage for the next chapter in Ferrari's legendary journey, one that would ultimately lead to the birth of Ferrari Automobili and the creation of some of the world's most iconic sports cars.

Soon after its inception, an enticing opportunity presented itself—one that would lay the foundation for Ferrari's resurgence in the racing world. The 1940 Mille Miglia, scheduled for April 28, was on the horizon.

However, due to prevailing conditions in Italy, the traditional route from Brescia to Rome and back was altered. The Brescia auto club organized the "Gran Premio Brescia della Mille Miglia" on a 103-mile triangular course, covering a distance of 927 miles over nine laps. This was a close approximation of the original thousand-mile race.

Substantial monetary rewards were at stake, with a prize of 10,000 lire (the former monetary unit of Italy and Malta and the currency of modern Turkey) for victory in each of five classes and an additional incentive from Fiat—a 5,000 lire prize for a class win by a car that was a Fiat or at least Fiat-based.

Ferrari and his team at AAC saw this as the perfect opportunity to make their mark in the racing world once again, setting the stage for an dust-raising comeback in the 1940 Mille Miglia.

A Play On The Alfa Romeo Tipo 158

With the 1940 Mille Miglia race only four months away, Enzo Ferrari found himself facing a daunting task: building suitable cars for his friend Lotario Rangoni Machiavelli and the promising auto racer Alberto Ascari.

The idea for a 1.5-liter car in this category had been discussed near the end of 1939, and at a Christmas Eve dinner party, Ferrari committed to the project.

Leading the car-design efforts was Alberto Massimino, a skilled engineer with vast experience, who had previously worked on projects such as the Alfa Romeo Tipo 158 and the engine of the Tipo 316 Grand Prix car.

To meet the tight deadline and meet the criteria for a potential Fiat prize, Ferrari's team decided to use a Fiat 508 C as their starting point. While the chassis was reinforced, key components like the brakes, live rear axle, steering, and Dubonnet independent front suspension remained untouched.

The transmission, however, received new gears with more suitable ratios. The heart of the car, the power unit, underwent extensive design and fabrication. Massimino ingeniously created a straight-eight engine based on the 1.1-liter 508 C Fiat's four-cylinder engine.

By maintaining the same 68 mm bore but shortening the stroke from 75 to 60 mm, he crafted an oversquare in-line eight engine with a displacement of 1,496 cc. This involved casting an aluminum cylinder block by Bologna's Fonderia Calzoni, Ferrari's trusted supplier.

Additionally, a new one-piece sump was designed to accommodate a "semi-dry-sump" lubrication system. The engine featured ferrous liners for the cylinders and two suitably ported Fiat 508 C cylinder heads. Cooling was enhanced with a larger water pump.

Related Reading: The Legacy Of The Prancing Horse: An In-depth Study on Historic Ferrari Models

Retained from the Fiat design was the pushrod and rocker overhead valve gear, concealed under a one-piece aluminum rocker cover. A new five-bearing crankshaft and matching camshaft, both designed by Massimino, were manufactured in Ferrari's well-equipped former Scuderia workshop.

The engine drew its breath through four downdraft Weber 30 DR 2 carburetors and relied on a single Marelli distributor to serve all eight cylinders. With a compression ratio of 7.0:1, an improvement over the original 508 C, this innovative engine delivered 72 to 75 hp at 5,500 rpm.

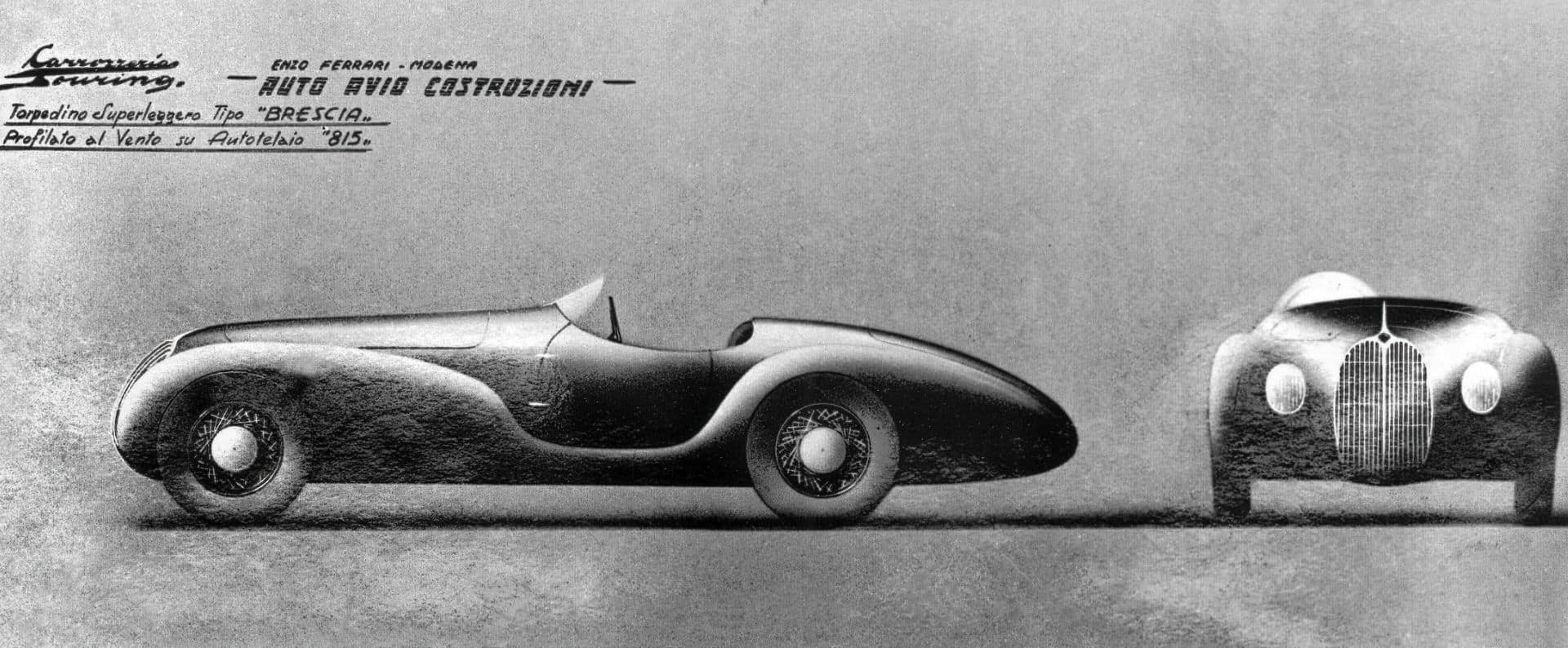

For the car's body design, Ferrari enlisted the expertise of Felice Bianchi Anderloni, the head of Milan's Carrozzeria Touring, one of Italy's forward-thinking coachbuilders.

Ferrari's request was clear: he wanted a car that could be unmistakably recognized as a Ferrari at a glance, hinting at his aspirations for future production vehicles with a touch of luxury.

Felice Anderloni and his team at Touring began with initial sketches, refining them with the help of "visualizers" who transformed concepts into detailed renderings. Their designs included not only a sports-racer but also a more formal cabriolet version.

After some experimentation with a less distinctive front end, they settled on a design featuring a pear-shaped grille, which, when combined with new headlamps, added a distinct character to the AAC's inaugural offering.

This car became known as the Tipo 815, playfully reversing the name of the Alfa Romeo Tipo 158, another 1.5-liter eight-cylinder racer.

The Prancing Horse Came Early

To ensure aerodynamic efficiency, a 1:10-scale model of the chosen design underwent wind tunnel analysis. Alberto Ascari, often present around the workshops, showed keen interest in every detail as the cars took shape.

While Rangoni Machiavelli's car received some elaborate trimmings, Ascari's car adhered to the sports-racing tradition with a more minimalistic approach.

The construction method employed Touring's "Superleggera" technique, utilizing a network of tubes over which closely fitted a lightweight alloy of magnesium and aluminum called Itallumag 35.

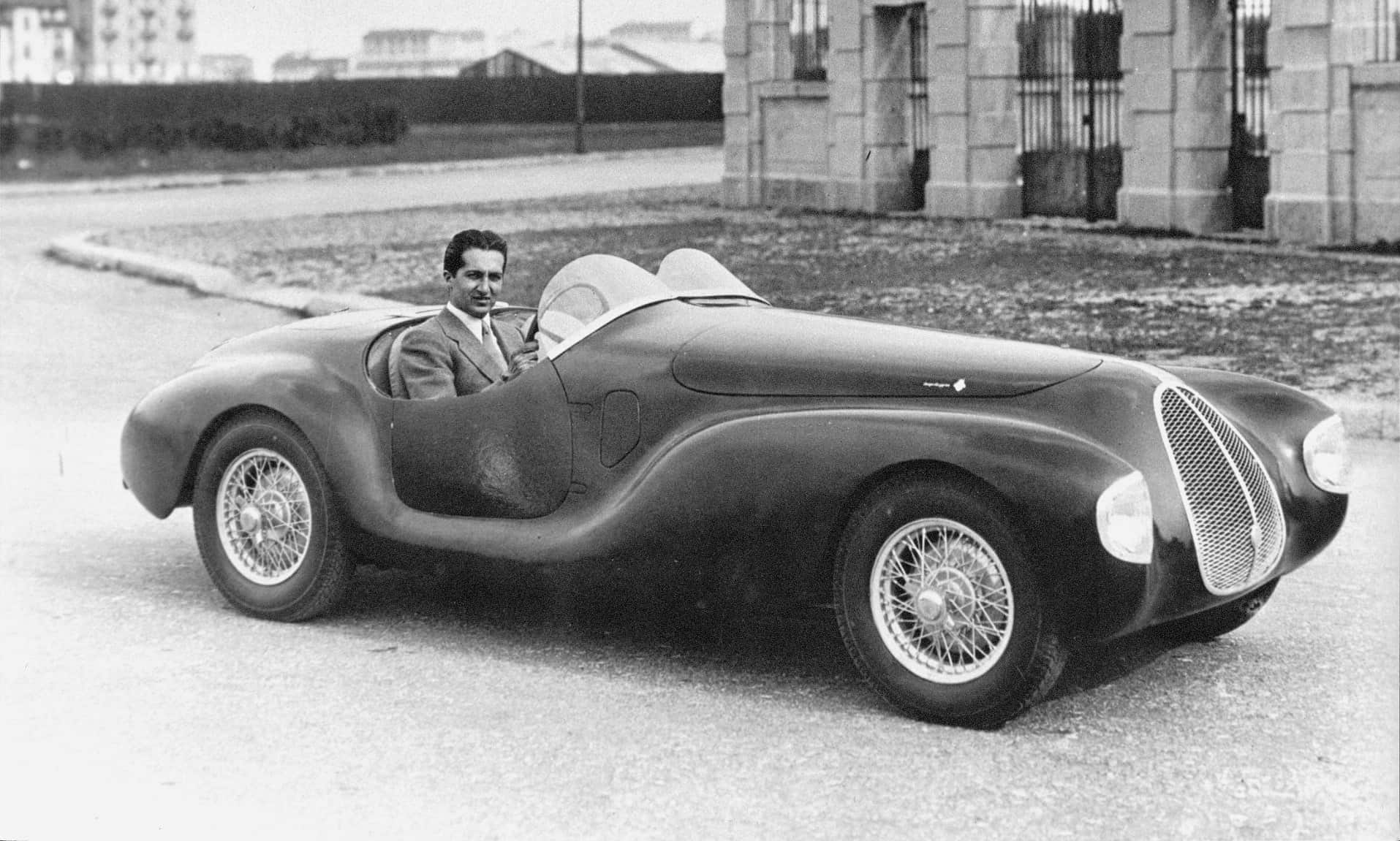

The entire body weighed a mere 119 pounds, contributing to the car's dry weight of 1,177 pounds. Its wheelbase measured 95.3 inches, with a track width of 48.8 inches. Borrani wire wheels with Rudge hubs were fitted with Pirelli Stella Bianca tires measuring 5.50 x 15 inches.

The fuel tank had a capacity of 23.8 gallons, all meticulously designed and assembled to create a racing machine poised for the grueling challenge of the 1940 Mille Miglia.

The saga of the Tipo 815, the experimental racer created in a hurry for the 1940 Mille Miglia, was marked by both triumphs and disappointments. The first completed 815 underwent extensive testing on public roads, with Enrico Nardi at the wheel.

Touring's favored testing routes stretched between Milan and Como, and between Milan and Bergamo. The cars were covered in felt ribbons, followed closely by a second car with a photographer on board to capture airflow patterns. The two cars had distinct designs, with Rangoni's featuring a longer tail. At least one of them proudly displayed a tiny prancing horse and the AAC initials above its grille, a nod to their maker's racing aspirations.

A Brilliant Start To A Hasty Failure

In a cautious move, Enzo Ferrari provisionally entered the cars for the race just two weeks before the event. Nonetheless, both Tipo 815s were ready for the grueling challenge of the Mille Miglia.

The race kicked off with the obligatory speeches from a Fascist party official, and Alberto Ascari's Tipo 815, serial number 021 with race number 66, set off at 6:21 am, followed closely by Rangoni's sister car, serial number 020.

Ascari, donning a Nuvolari-like kit with a motorcyclist's sleeveless waistcoat over his jersey, quickly overtook his teammate and took the lead in their class.

However, his promising run was cut short when one of the Fiat-made rocker arms failed during his second lap, forcing him to retire.

On the other hand, Lotario Rangoni Machiavelli fared better in the car that had undergone more thorough pre-race testing. He took over the class lead and even set a 1.5-liter lap record at an impressive 91 mph. However, with just two and a half laps to go, disaster struck as the transmission failed, dashing their hopes.

Ferrari summed up this experience by stating, "The experiment that started so brilliantly ended in failure, largely because the car had been built too hastily. Nor had there been time to test it thoroughly."

Despite the setbacks in the 1940 Mille Miglia, Alberto Ascari managed to sell his Tipo 815 for a handsome sum of 42,000 lire ($27,144.98 in today’s money) in February 1943, nearly doubling his initial investment.

The car's new owner, Enrico Beltracchini from Milan, entered it in races, with mixed results, including several retirements and a few respectable finishes. As for Rangoni Machiavelli's car, its fate took a more tragic turn.

Following an accident, his Tipo 812 was sent to a scrapyard, albeit for storage rather than immediate dismantling. In a cruel twist of fate, the marquis met a fatal crash while test-flying an airplane in 1942.

The car eventually fell into the hands of his brother, Rolando, who embarked on a mission to recover it in 1958. However, when he returned to collect this historic long-tailed "First Ferrari," he discovered that it had been unceremoniously scrapped in the intervening years.

The Tipo 815 Still Lives

On a brighter note, the short-tailed Ascari 815, which passed from Beltracchini to Emilio Fermi-Storchi, found a home in a small museum near Modena. Later, it was acquired by Mario Righini and Domenico Gentili, who undertook a substantial restoration.

The bodywork was refreshed by Campana di Modena, while Gianni Torrelli of Campagnolo in Reggio Emilia meticulously rebuilt the engine and drive line.

The car made a triumphant return to the racing scene in the 1991 Mille Miglia Retrospective, showcasing Enzo Ferrari's unwavering determination to leave his mark on the world of motor racing.

In the annals of automotive history, these Tipo 815s may not have been the most successful or well-known Ferraris, but they hold a unique and revered place as the "first Ferraris" – a testament to Enzo Ferrari's vision, determination, and the relentless pursuit of his racing dreams.

Sources: RevInstitute.Org